Caught in the dance

Mina Masoumi

24 NOVEMBER 2023

- 24 DECEMBER 2023

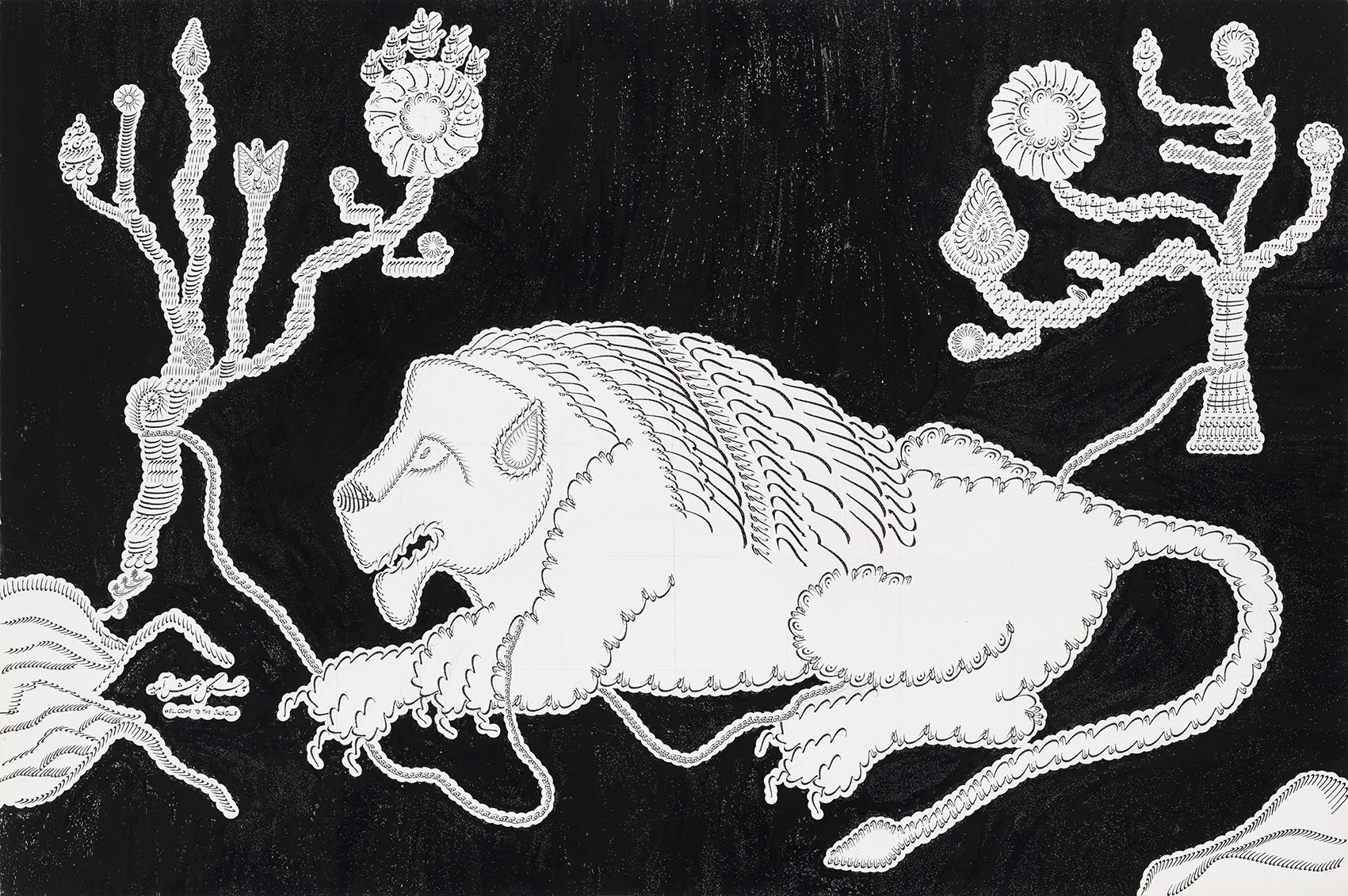

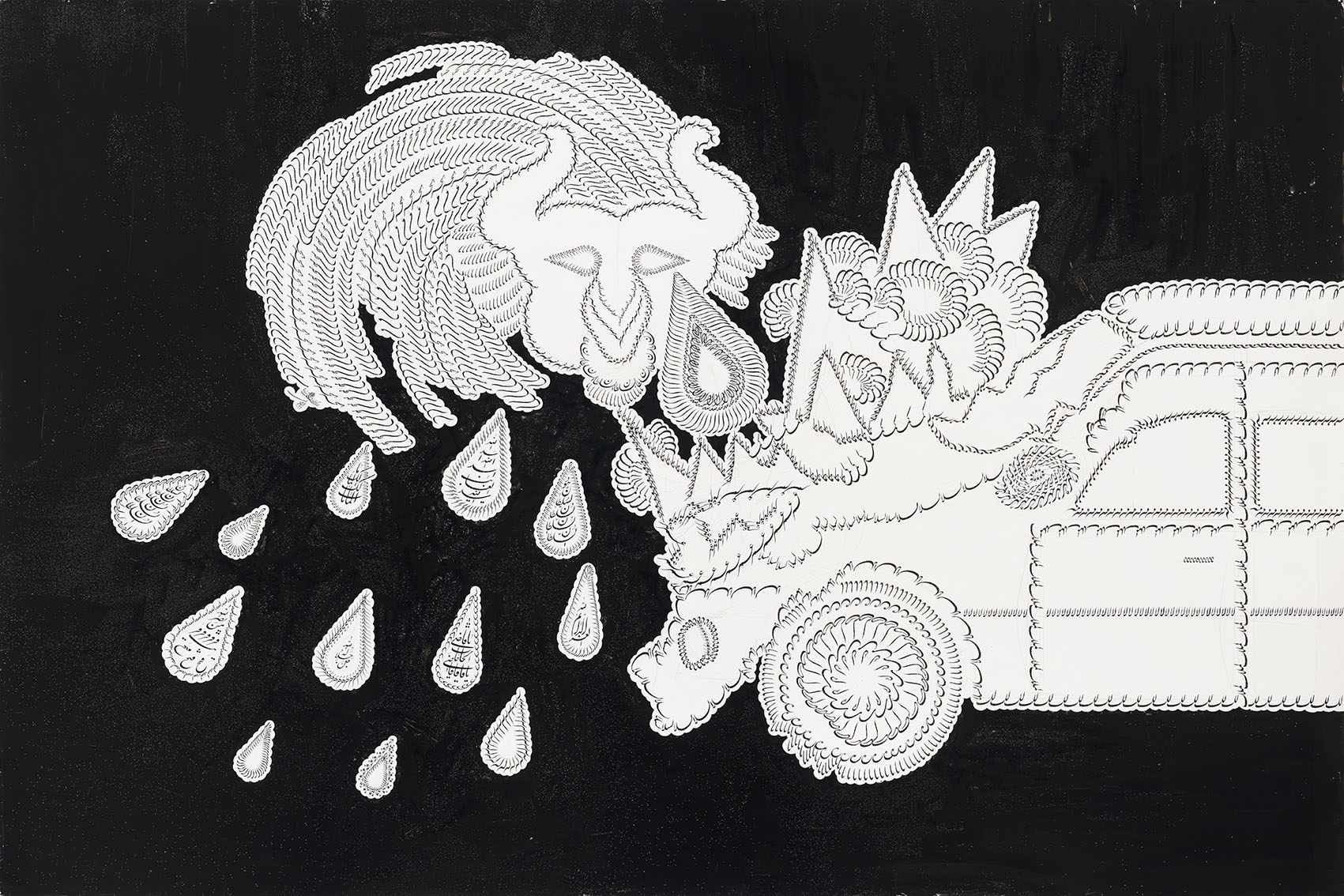

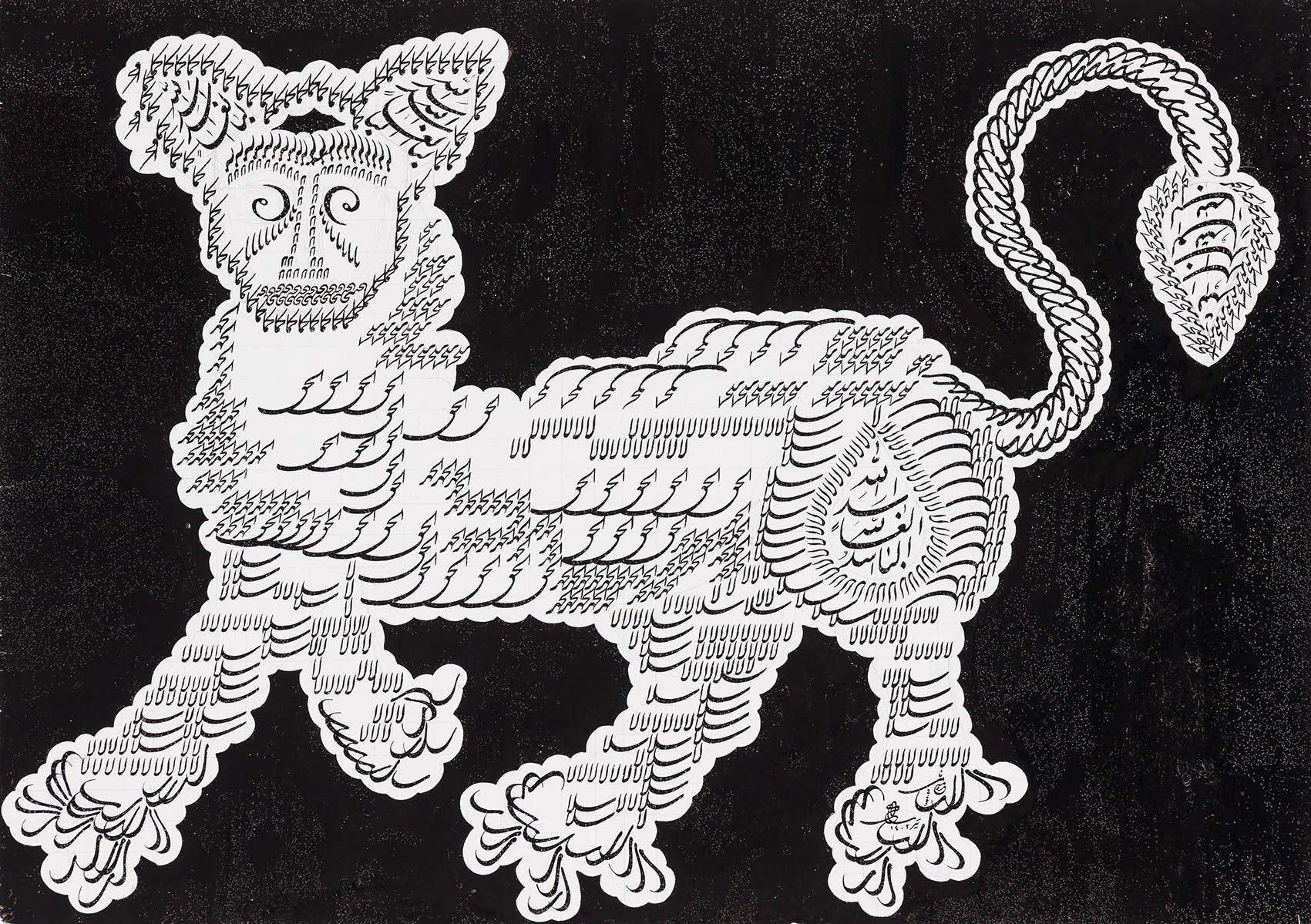

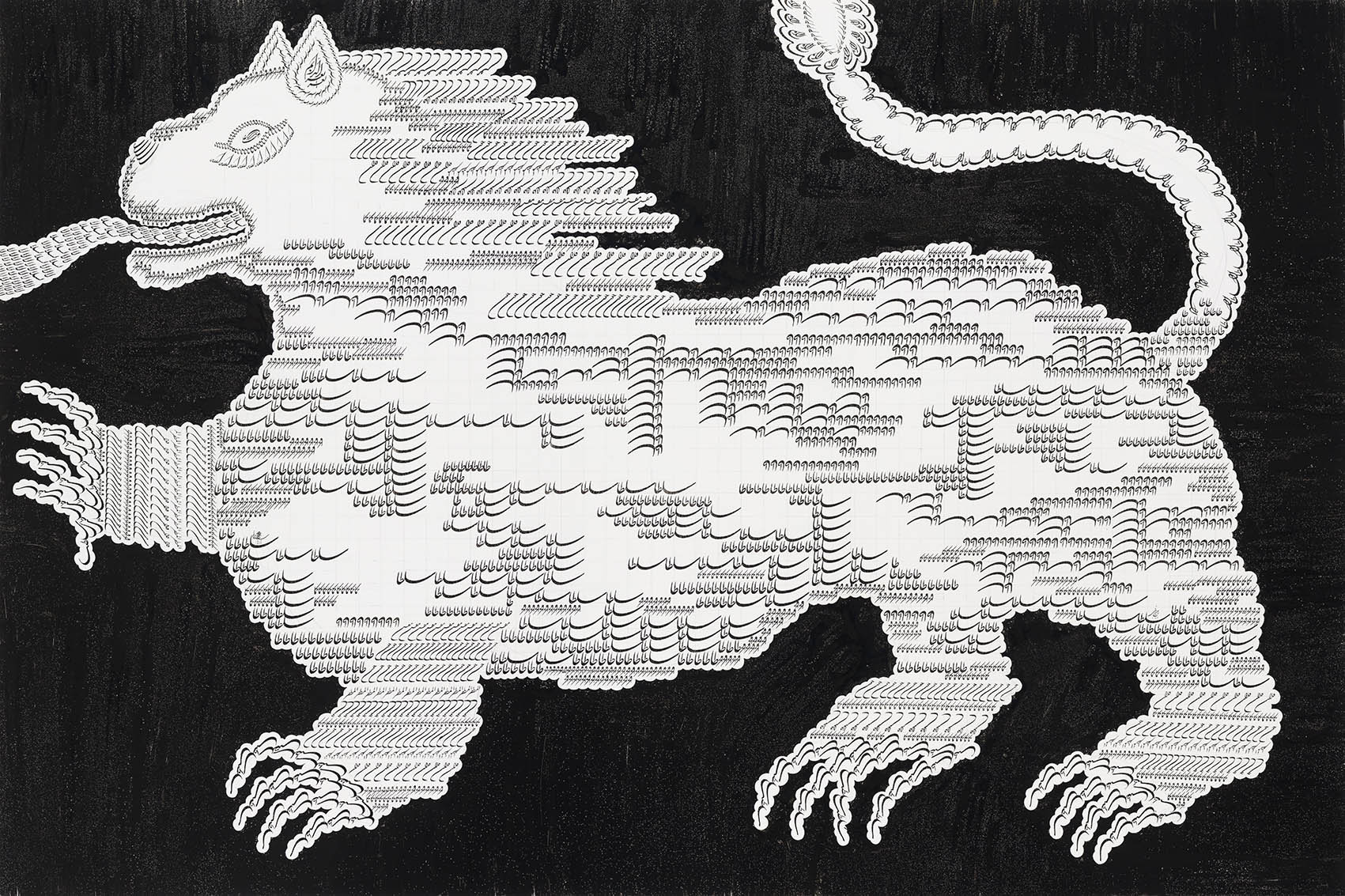

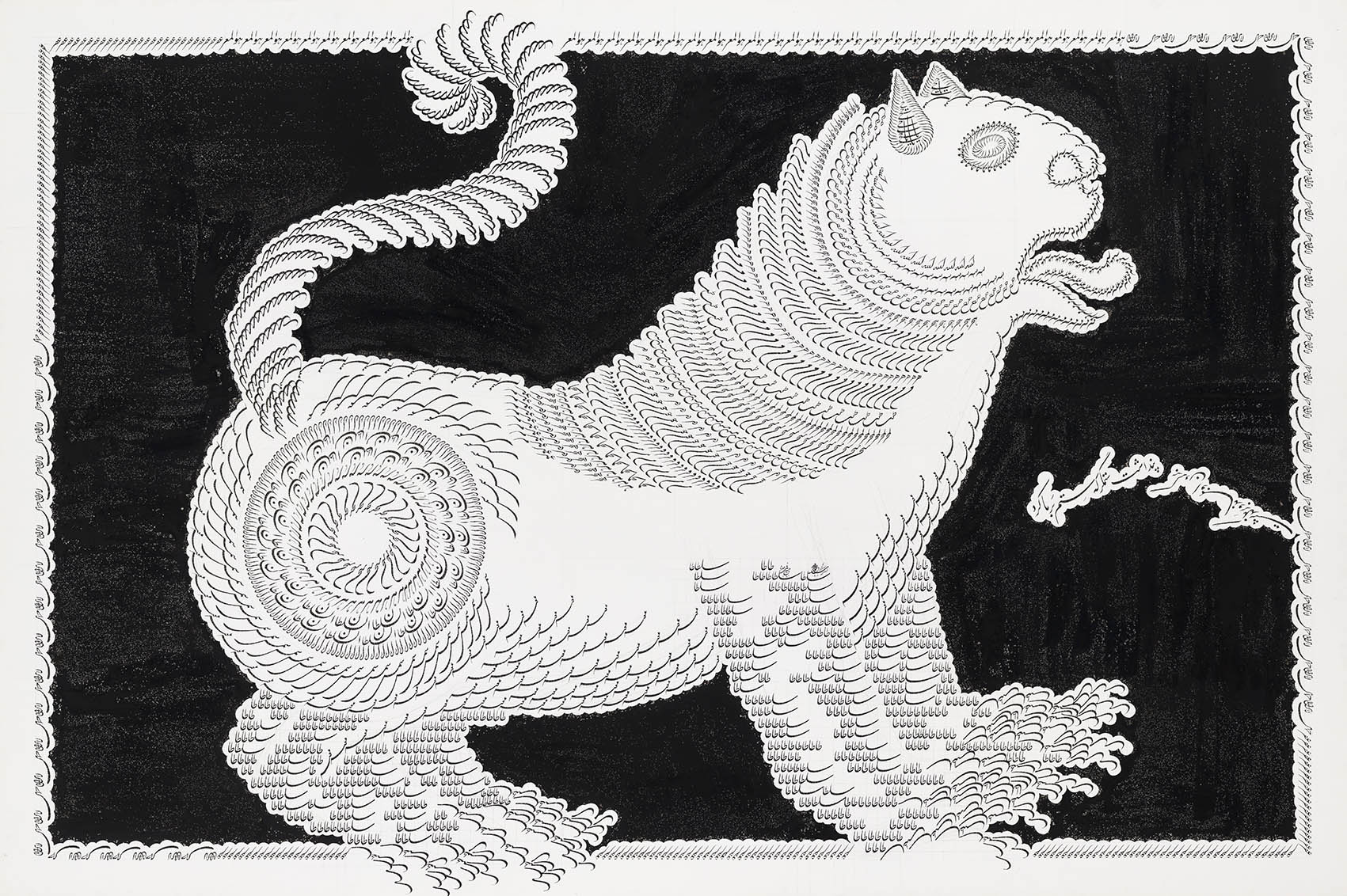

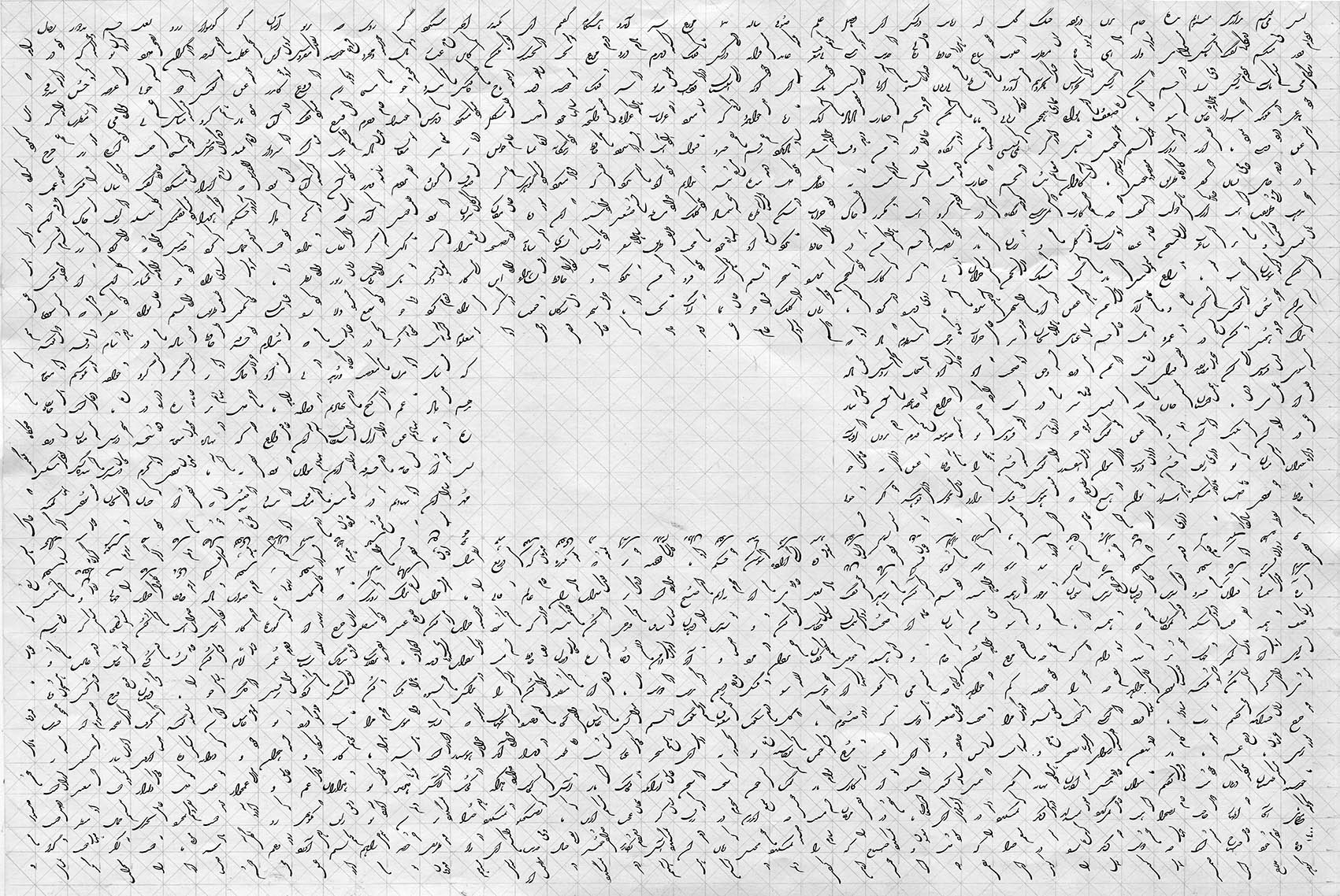

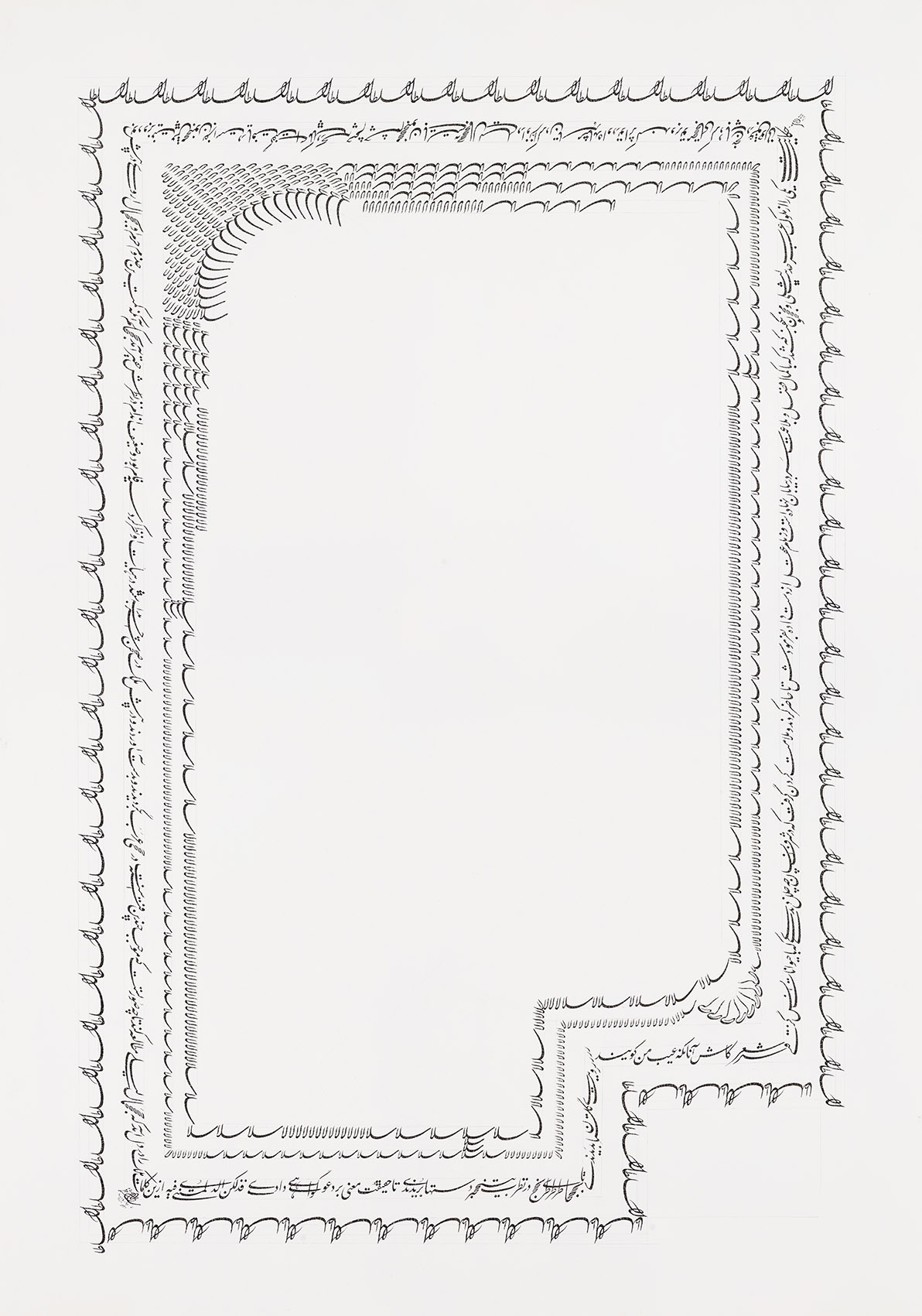

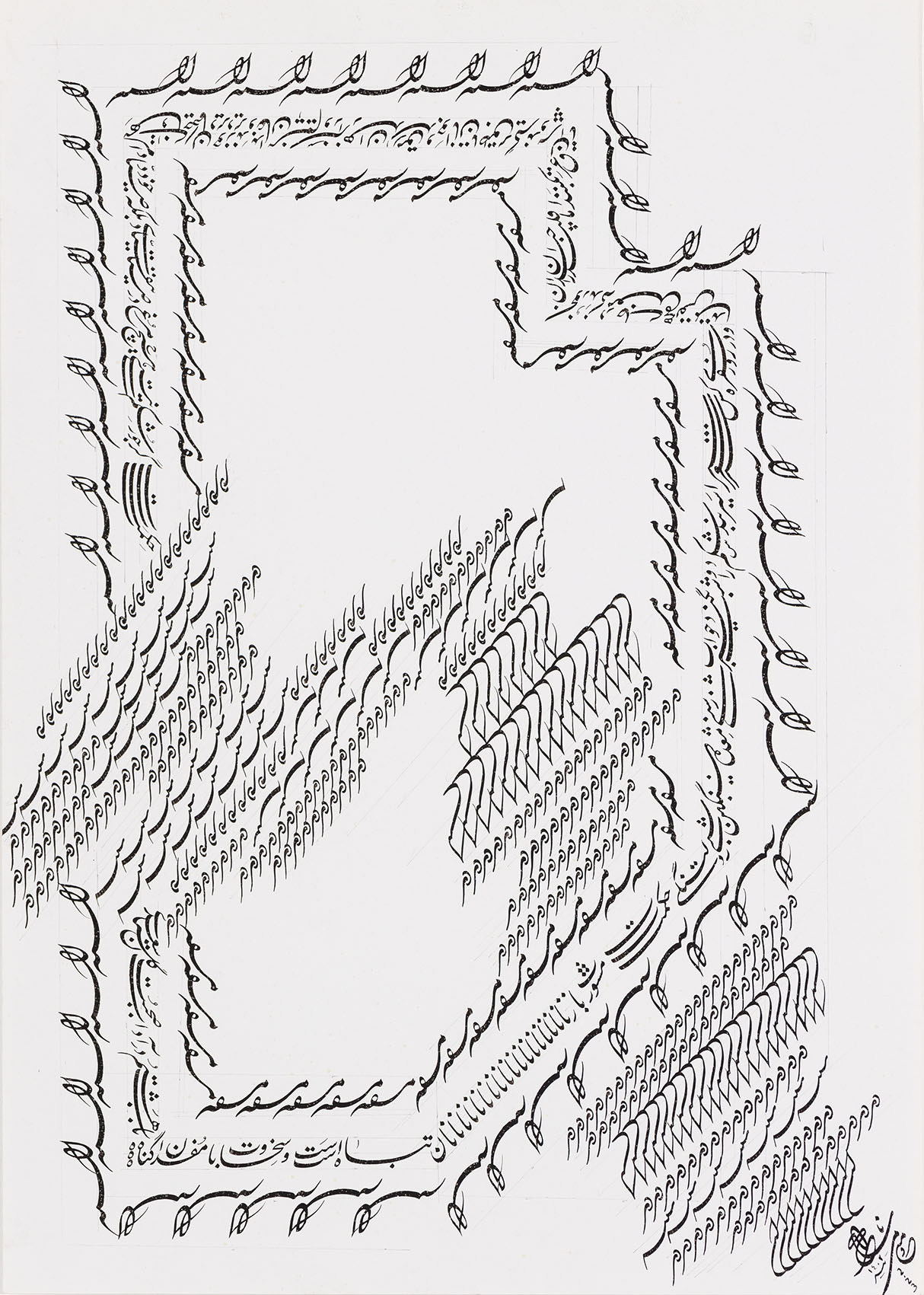

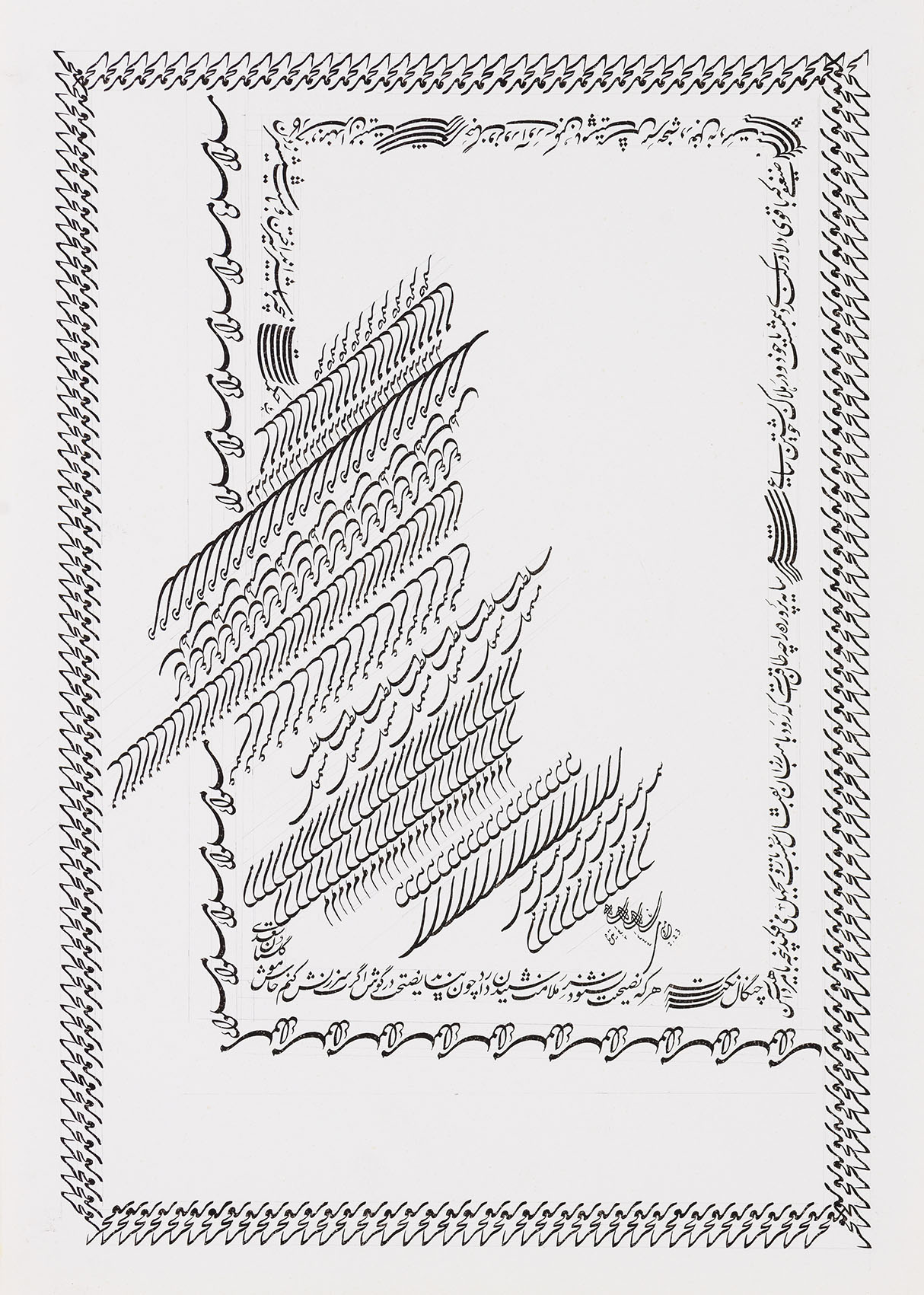

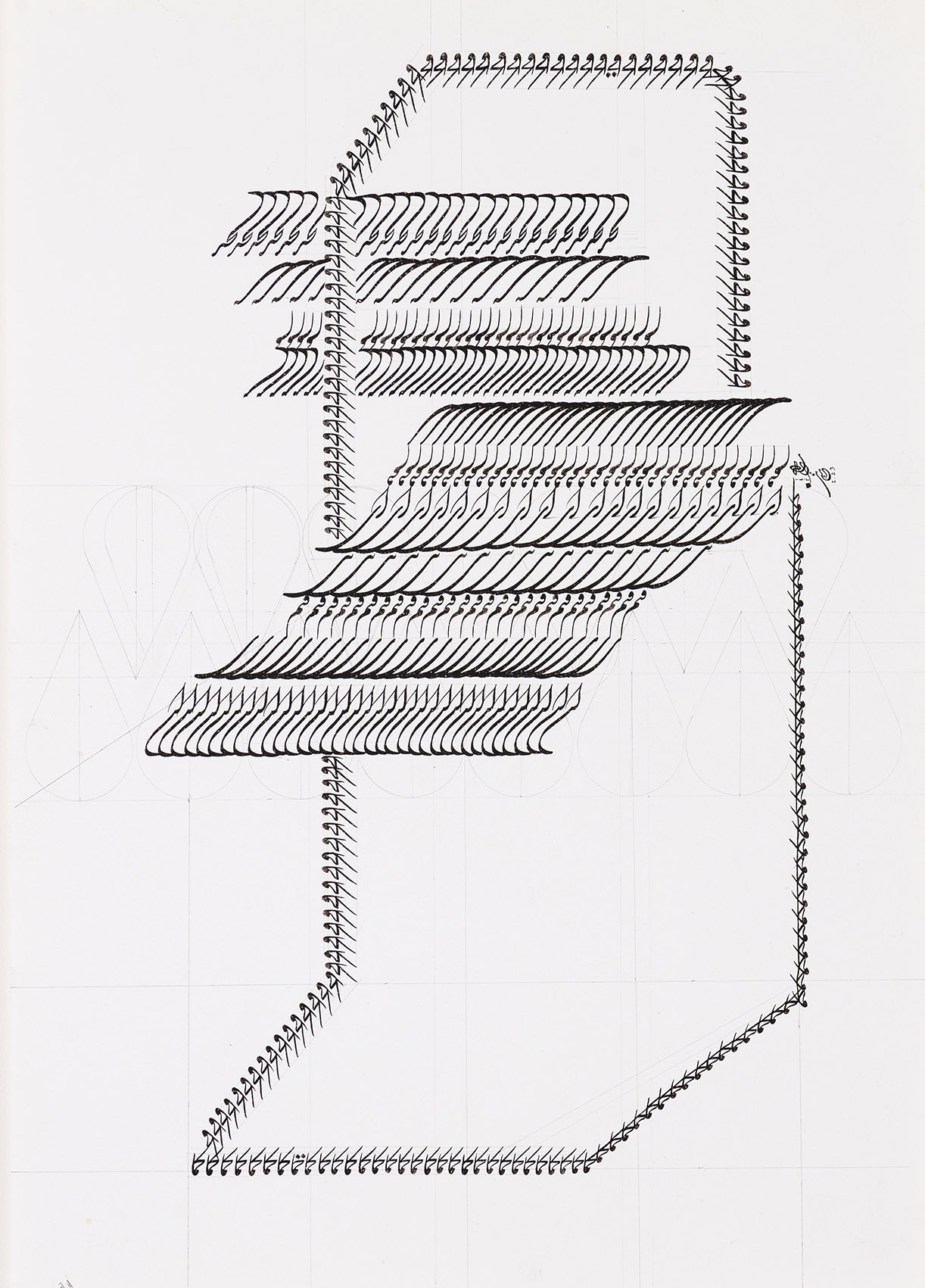

Imagine that you have selected the paintbrush tool in a computer software like Photoshop, and have also selected black color for the brush. Next, there is a section for selecting the type of brush. There are different options available to you. You can choose a pen-like brush with different diameters, or change its transparency, or select a paintbrush or calligraphy pen with your desired thickness. You can even choose different textures. Hundreds of choices are available to you. Now, continue this imaginary path and assume that the options you have selected for the brush’s tip are Nastaliq and Shekasteh-Nastaliq hands. You shake the brush like a magician and your design appears on the page with the texture of your desired words. You draw clouds made of the Persian letter Sīn or the word [Topol] and drops made of the same word fall down like rain. You have made raindrops out of the word [Topol], only smaller in size. You enjoy this a bit more and continue until you have a delightful experience. This experience has a lot of technical similarities to what Mina Masoumi does.

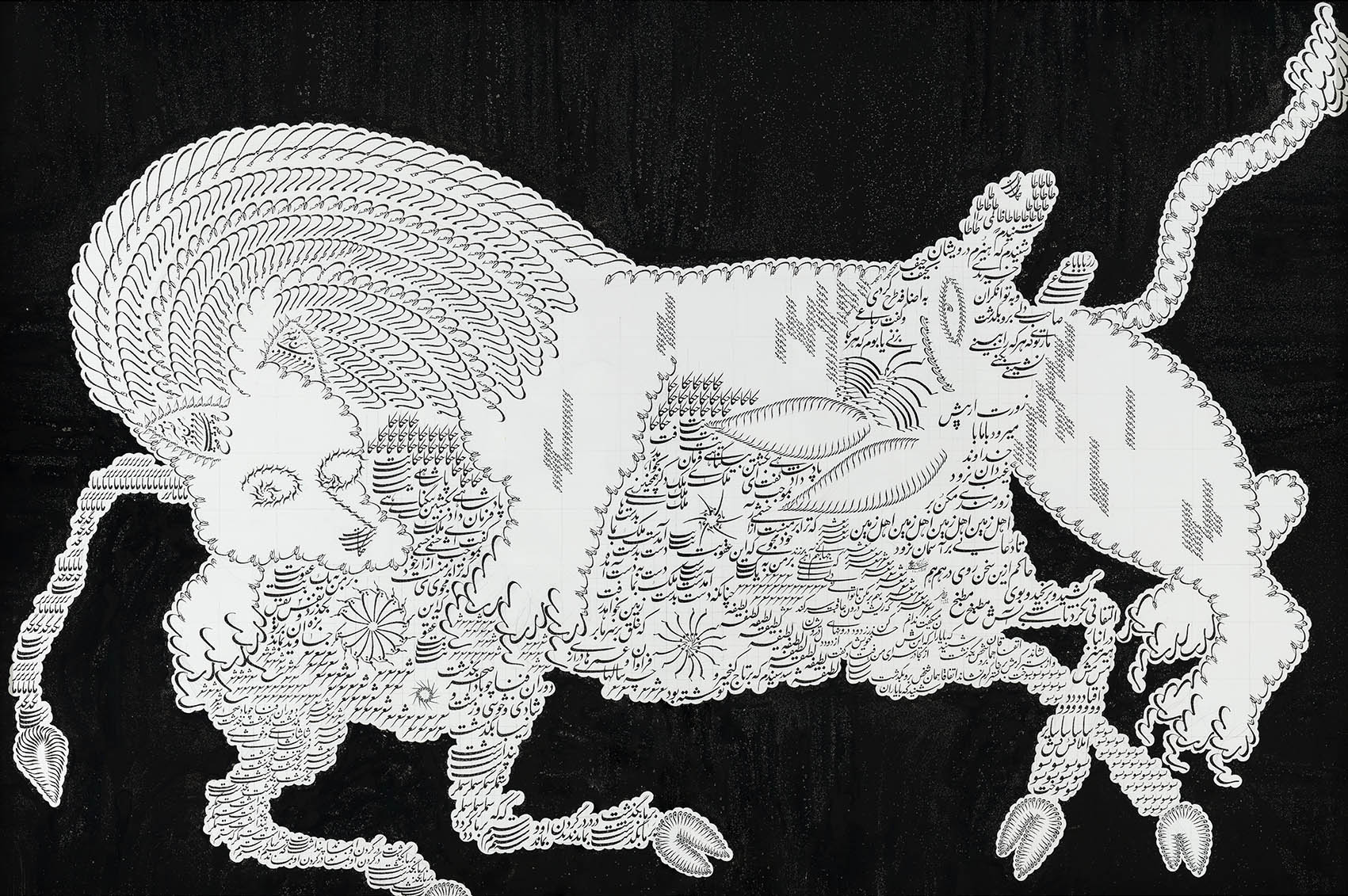

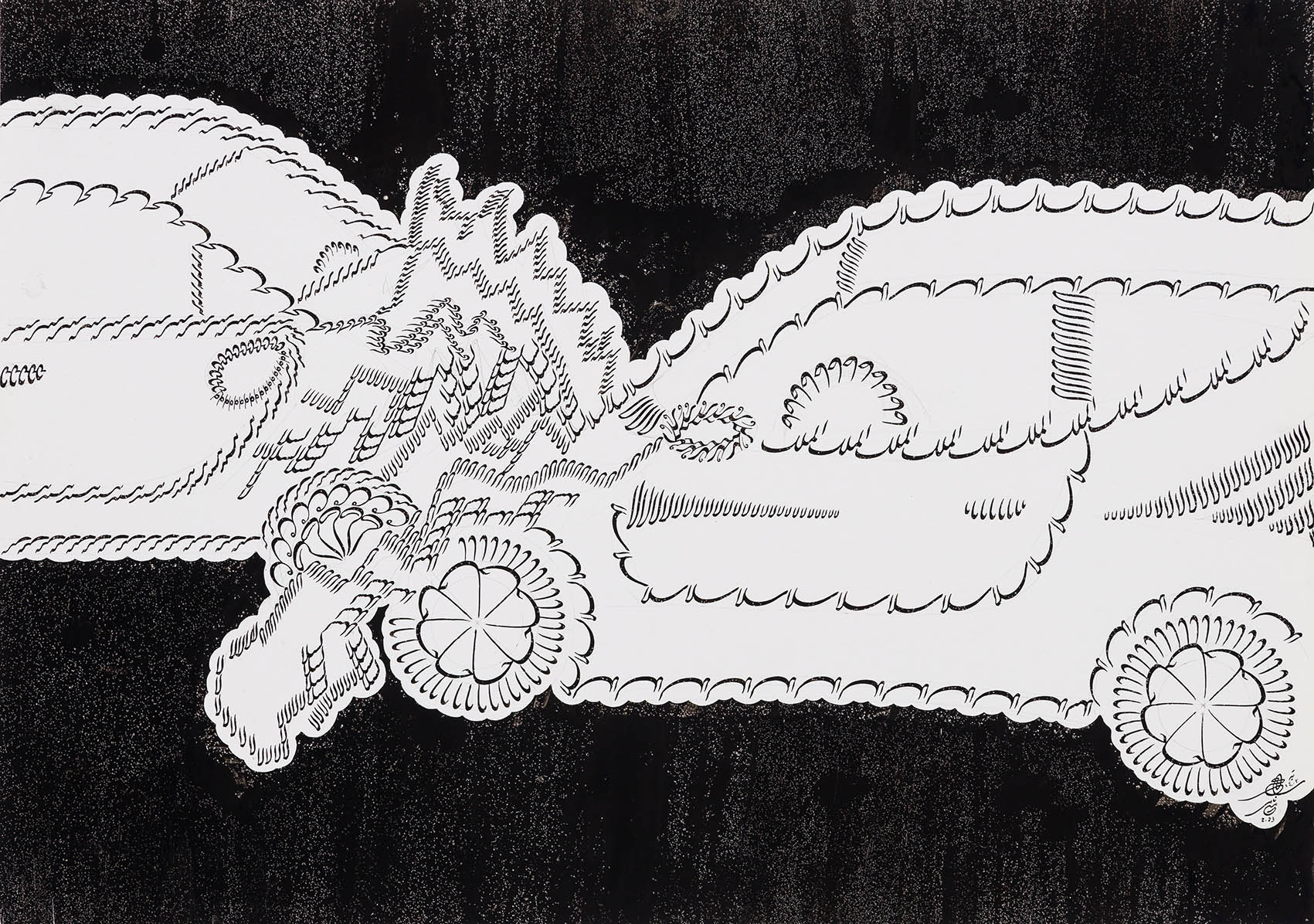

Masoumi’s pen here is not a calligraphy pen, but rather calligraphy itself. The texture of her pen is her own Shekasteh-Nastaliq script and she makes crosshatches with her very words. The difference between the artist’s experience and yours is that there is no software involved for the artist. When she starts working, she would need to invest considerable time and effort to reach results. She needs more or less an initial idea and sketch of the image she wants to create. For this kind of process, we can use an example from an Iranian poet, contrary to the author’s desire in this text: in the words of Rumi, “You are my ball and you run by the desire of my mallet in my game; I follow you, although I control your moves”. What Masoumi does not have, unlike painting software, is the ability to return, undo, erase, and redo. This is what makes her work process and practice closer to this poem. This is not to emphasize on the difficulty of her work, the required accuracy, and the time spent on creating a single work, but rather it is to highlight the value of an artist’s intellectual practice and their process in creating an artistic work, that includes the ever-changing experience of creating and reimagining. Hard work and toil do not necessarily increase the value of a work of art, and perhaps could be a sign of weakness for the artist and the lack of other features in their practice.

Masoumi entered contemporary art via her practice and background in calligraphy. One can still trace the influence of Persian poetry and literature in her references and her Mashgh practices of appropriations and adaptations. Nevertheless, her work is neither Siāh-Mashgh (overlaying of calligraphic practices) nor Khat-Naghāshi (calligraphic painting). The realm of contemporary art provides Masoumi with the opportunity to use all of her forces to create an image and an idea. In the past, to create the content of a page of a book, the poet would give the text to the calligrapher, and after writing the text, the calligrapher would hand it over to the painter, and after finishing the painting, the painter would send the paper to the binder to make a worthy frame. Masoumi, whose palette is her calligraphic hand, has taken on all these roles in her work process. Her pen is made up of letters, words, and text. She utilizes both the untapped potential of calligraphy and type, and the meanings and sounds hidden in letters and words. Her work explores the relationship between these words in Persian writing and the formal relationships of composition, drawing, and dimension. This coherence of words and sentences with each other exists both in the details of the work and in its final general form. The reason behind this is the same type of production mechanism mentioned above.

On one hand, Mina Masoumi’s visual and semantic references are intertwined with Iranian history, culture, and literature. She studies the historical identity of the lion in Iranian culture and at the same time examines the role of the lion’s image on tablets, reliefs, and sculptures. She creates a work inspired by Saadi’s “On the Manners of Conversation” and in another work references words inscribed by the Ottomans on their weapons. On the other hand, her works have a deep connection with the inner workings of modern image processing devices. Processors use letter and word encoding both to produce and present images. They convert the original image into binary code and then send them to their final destination via radio waves, wires or satellites. They eventually provide us with a device that we can convert these codes back into an image. In a more primitive form, a decade or two ago, we sent a picture of a cat or a large heart made up of letters, numbers, and parentheses to our beloved ones on our early mobile phones. Now, the modern world has provided us with the ability to exchange more than just cats whose paws are made up of the letter M.

Masoumi presents the Persian language and script structure to the audience for them to read into her work. She establishes a unique relationship between sounds, word forms, and the narratives of the image. In the scene of two cars colliding or the image of a lion colliding with a car, or the hunting of a car by a lion and the failure of the lion in this pursuit, the complexities of sound and form are increased. Now, smoke, fire, tears, and the rotation of the four wheels on the paper all have sound, and they all synesthetically open the viewer’s other senses. The playback device for these sounds is the viewer themselves —they can utter the sound of letters so that they themselves or someone else can hear them, or can silently imagine the sound of words and events.

Shabahang Tayyari, November 2023

در آداب رقص و گرفتاری

مینا معصومی

تصور کنید که در یک نرمافزار کامپیوتری مانند فتوشاپ ابزار قلم نقاشی را انتخاب کردهاید و رنگ مشکی را هم برای قلم برمیگزینید. در ادامه قسمتی هم وجود دارد برای انتخاب نوع قلم. گزینههای متفاوتی در پیش روی شماست. میتوانید قلمی مانند خودکار با قطرهای متفاوت انتخاب کنید و یا شفافیت آن را تغییر دهید و یا قلمی مانند قلمموی نقاشی و یا قلم خوشنویسی انتخاب کنید با پهنای دلخواه. حتی بافتهای مختلفی را میتوانید برگزینید و صدها انتخاب دیگر. حالا تصور را ادامه دهید و فکر کنید گزینهای که برای نوک قلمموی نقاشی انتخاب کردهاید خط و نوشتار نستعلیق و شکسته نستعلیق است. شما مانند یک جادوگر قلم را روی صفحه تکان میدهید و طرح شما با بافتار کلمات دلخواه پدیدار میشود. ابرهایی میکشید که با حروف سین و یا کلمهی "تپل" ساخته شدهاند و از آن قطرههای باران به پایین میریزد. قطرههای باران را هم با کلمهی "تپل" ساختهاید ولی با ابعاد کوچکتر. کمی ذوق میکنید و ادامه میدهید و در پایان تجربهی دلانگیزی به شما دست میدهد. این تجربه شباهت فنی زیادی دارد به کاری که مینا معصومی انجام میدهد.

قلم معصومی در اینجا قلم خوشنویسی نیست بلکه خود خوشنویسی است. بافت قلمش خود خط شکسته نستعلیق است و با خود خط و کلمهها هاشور میزند. تفاوت تجربهی هنرمند با تجربهی شما این است که برای هنرمند نرمافزاری در کار نیست. وقتی شروع به کار میکند امکان اینکه به سرعت به نتیجه برسد را ندارد. کم و بیش نیاز دارد به اندکی تصور اولیه و حدس و گمان از تصویری که میخواهد به ثمر برساند. برای این شکل از روند کاری میتوانیم برخلاف میل نویسنده از ادیبان ایرانی در این متن مثال بیاوریم. "گوی منی و میدوی در چوگان حکم من / در پی تو همی دوم گرچه که میدوانمت" از مولوی. امکانی که معصومی برخلاف نرمافزار نقاشی ندارد امکان بازگشت و پاک کردن و دوباره انجام دادن است. همین امر است که روند کارگاهی او را به این شعر نزدیکتر میکند. صحبت از سختی کار و دقت و سپری کردن زمانی طولانی برای ساختن یک اثر نیست. حرف از طی کی کردن مسیر و اندیشیدن برای به انجام رساندن است و مواجهه با پستی و بلندی های آن مسیر قسمتی از معنای آن است. سختی کشیدن و مشقت بردن در به وجود آوردن اثر هنری ارزش محسوب نمیشود و چه بسا نشانهی ضعف هنرمند و تهی بودن هنرمند از ویژگی های دیگر است.

معصومی از بستر خوشنویسی وارد فضای هنر معاصر شده است. هنوز ارجاعاتش را به ادبیات و شعر فارسی را دارد و شکلی از مشق کردن آن را در کارهایش حفظ کرده. اما نه سیاه مشق است و نه خط نقاشی. بستر هنر معاصر این امکان را برای معصومی فراهم میکند تا از تمام نیروها برای ساختن تصویر و اندیشه بهره بگیرد. در ایام دورتر برای ساختن محتوای یک صفحه از کتاب، شاعر متن را به کاتب میداد و کاتب بعد از کتابت آن را به دست نقاش می سپرد و نقاش بعد از اتمام نقشش صفحهی کاغذ را به سوی تسمهکش راهی میکرد تا قابی در شان و منزلت این همه هنر بسازد. معصومی که پالت نقاشیاش خط است، تمام این نقش ها را در مسیر کاریاش به عهده گرفته است. قلم او از حروف و کلمات و متن تشکیل شده است. هم از پتانسیل نهفته در خود خط استفاده میکند و هم از معناها و آواهای حروف و کلمات. ارتباط میان این کلمات در نوشتار فارسی و ارتباط فرمی و کشیدگی و ابعاد حروف در ارتباط با سوژه کار اوست. این تنیدگی کلمات و جملات با یکدیگر هم در جزئیات کار وجود دارد و هم در شکل نهایی آن. دلیلش همان نوع مکانیزم تولید است که در بالا به آن اشاره شده است.

مینا معصومی

تصور کنید که در یک نرمافزار کامپیوتری مانند فتوشاپ ابزار قلم نقاشی را انتخاب کردهاید و رنگ مشکی را هم برای قلم برمیگزینید. در ادامه قسمتی هم وجود دارد برای انتخاب نوع قلم. گزینههای متفاوتی در پیش روی شماست. میتوانید قلمی مانند خودکار با قطرهای متفاوت انتخاب کنید و یا شفافیت آن را تغییر دهید و یا قلمی مانند قلمموی نقاشی و یا قلم خوشنویسی انتخاب کنید با پهنای دلخواه. حتی بافتهای مختلفی را میتوانید برگزینید و صدها انتخاب دیگر. حالا تصور را ادامه دهید و فکر کنید گزینهای که برای نوک قلمموی نقاشی انتخاب کردهاید خط و نوشتار نستعلیق و شکسته نستعلیق است. شما مانند یک جادوگر قلم را روی صفحه تکان میدهید و طرح شما با بافتار کلمات دلخواه پدیدار میشود. ابرهایی میکشید که با حروف سین و یا کلمهی "تپل" ساخته شدهاند و از آن قطرههای باران به پایین میریزد. قطرههای باران را هم با کلمهی "تپل" ساختهاید ولی با ابعاد کوچکتر. کمی ذوق میکنید و ادامه میدهید و در پایان تجربهی دلانگیزی به شما دست میدهد. این تجربه شباهت فنی زیادی دارد به کاری که مینا معصومی انجام میدهد.

قلم معصومی در اینجا قلم خوشنویسی نیست بلکه خود خوشنویسی است. بافت قلمش خود خط شکسته نستعلیق است و با خود خط و کلمهها هاشور میزند. تفاوت تجربهی هنرمند با تجربهی شما این است که برای هنرمند نرمافزاری در کار نیست. وقتی شروع به کار میکند امکان اینکه به سرعت به نتیجه برسد را ندارد. کم و بیش نیاز دارد به اندکی تصور اولیه و حدس و گمان از تصویری که میخواهد به ثمر برساند. برای این شکل از روند کاری میتوانیم برخلاف میل نویسنده از ادیبان ایرانی در این متن مثال بیاوریم. "گوی منی و میدوی در چوگان حکم من / در پی تو همی دوم گرچه که میدوانمت" از مولوی. امکانی که معصومی برخلاف نرمافزار نقاشی ندارد امکان بازگشت و پاک کردن و دوباره انجام دادن است. همین امر است که روند کارگاهی او را به این شعر نزدیکتر میکند. صحبت از سختی کار و دقت و سپری کردن زمانی طولانی برای ساختن یک اثر نیست. حرف از طی کی کردن مسیر و اندیشیدن برای به انجام رساندن است و مواجهه با پستی و بلندی های آن مسیر قسمتی از معنای آن است. سختی کشیدن و مشقت بردن در به وجود آوردن اثر هنری ارزش محسوب نمیشود و چه بسا نشانهی ضعف هنرمند و تهی بودن هنرمند از ویژگی های دیگر است.

معصومی از بستر خوشنویسی وارد فضای هنر معاصر شده است. هنوز ارجاعاتش را به ادبیات و شعر فارسی را دارد و شکلی از مشق کردن آن را در کارهایش حفظ کرده. اما نه سیاه مشق است و نه خط نقاشی. بستر هنر معاصر این امکان را برای معصومی فراهم میکند تا از تمام نیروها برای ساختن تصویر و اندیشه بهره بگیرد. در ایام دورتر برای ساختن محتوای یک صفحه از کتاب، شاعر متن را به کاتب میداد و کاتب بعد از کتابت آن را به دست نقاش می سپرد و نقاش بعد از اتمام نقشش صفحهی کاغذ را به سوی تسمهکش راهی میکرد تا قابی در شان و منزلت این همه هنر بسازد. معصومی که پالت نقاشیاش خط است، تمام این نقش ها را در مسیر کاریاش به عهده گرفته است. قلم او از حروف و کلمات و متن تشکیل شده است. هم از پتانسیل نهفته در خود خط استفاده میکند و هم از معناها و آواهای حروف و کلمات. ارتباط میان این کلمات در نوشتار فارسی و ارتباط فرمی و کشیدگی و ابعاد حروف در ارتباط با سوژه کار اوست. این تنیدگی کلمات و جملات با یکدیگر هم در جزئیات کار وجود دارد و هم در شکل نهایی آن. دلیلش همان نوع مکانیزم تولید است که در بالا به آن اشاره شده است.

ارجاعات تصویری و معنایی کارهای معصومی از یک سو در تاریخ و فرهنگ و ادبیات ایران گره خورده است. با هویت تاریخی شیر در فرهنگ ایرانی سر و کار دارد و همزمان نقش صورت شیر بر روی لوح ها و نقش برجستهها و سردیسها را واکاوی میکند. کاری را با حکایت سعدی "در آداب صحبت" می سازد و در کاری دیگر به کلماتی ارجاع میدهد که عثمانیان بر روی ابزار آلات جنگی مینوشتند. از سوی دیگر، کارهای او ارتباط عمیقی با ساختار دستگاههای مدرن پردازش تصویر دارد. پردازشگرها هم در تولید تصویر و هم در ارائهی تصویر از کدگذاری حروف و کلمات استفاده میکنند. تصویر اولیه را به کدهای صفر و یک تبدیل میکنند و بعد آنها توسط موجهای رادیویی و یا سیم و ماهواره به مقصد نهایی ارسال میکنند. در انتها دستگاهی را به ما ارائه میدهند که این کدها را دوباره به تصویر بدل کنیم. به شکل ابتداییتر در یک یا دو دهه پیش ما عکس یک گربه و یا یک قلب بزرگ ساخته شده از حروف و اعداد و پرانتز را بر روی گوشیهای موبایل آن دوره برای معشوقمان میفرستادیم. حالا دنیای مدرنتر این قابلیت را برای ما فراهم کرده چیزهایی بیشتر از یک گربهای که پاهایش با حرف اِم انگلیسی ساخته شده رد و بدل کنیم.

معصومی دستگاه زبان و نوشتار فارسی را برای خوانش آثارش به مخاطب ارایه میدهد. ارتباط منحصر به فردی میان آواها و فرم کلمات و روایت تصویر برقرار میکند. در صحنه برخورد دو اتومبیل با هم و یا تصویر برخورد شیر با اتومبیل و یا شکار اتومبیل توسط شیر و ناکام ماندن شیر در این امر پیچیدگی آوایی و فرمی را بیشتر میکند. حالا دیگر دود و آتش و اشک و چرخش چرخ یک چهار چرخه روی کاغذ صدا هم دارد و حساسیتهای دیگری را در بیننده فعال میکند. دستگاه پخش این آواها خود تماشاگر است. هم میتواند با دهانش آوای حروف را پخش کند تا خودش یا دیگری هم بشنود و یا بدون تولید صدا، تصوری از آوای کلمات و رخداد ها برای خود داشته باشد.

شباهنگ طیاری - آبانماه هزار و چهارصد دو شمسی